E-mentoring as a tool to make aid for trade more effective

Developing countries that create an institutional environment that is favourable to economic and technological change tend to benefit most from the effects of international trade liberalization.1 In contrast, countries that primarily focus on protecting vulnerable economic sectors with public sector subsidies tend to crowd out private sector investment.2

The public in affluent countries sees economic and technological change primarily as a threat rather than an opportunity, especially when it comes to social and environmental problems. As a consequence, policymakers in these countries tend to focus on shielding the poor from economic and technological change while refraining from promoting economic and social change through growth-oriented entrepreneurship.3 This has left a gap in competence among major donor agencies on how best to facilitate inclusive technology transfer and assist local entrepreneurship in promoting home-grown, sustainable growth in the developing world.

The Doha Ministerial Declaration made technical assistance and capacity building a key component of the development dimension of trade and set up a WTO work programme on Aid for Trade at the Sixth Ministerial Conference in Hong Kong in December 2005. Aid for Trade had the potential to enhance entrepreneurial infrastructure in poor countries. However, the task force formed to make Aid for Trade operational failed to come up with a clear vision. Instead, it restricts itself to monitoring existing development assistance activities, thereby largely relying on donor agency self-evaluation.4

The principal-agent problem in development assistance reflects the fact that donor agencies in affluent countries (the agent) primarily seek to please donors and taxpayers in their home countries (the principal) rather than developing country recipients.5 The taxpayer-influenced preference for protecting the vulnerable then leads to the design of development projects that aim to protect existing economic structures rather than facilitate economic change. All this prevents growth-oriented entrepreneurship, especially in least developed countries (LDCs) that desperately need it but are also highly dependent on foreign aid.6 Trade Negotiators should therefore seek the broadening of the definition of Aid for Trade in order to properly address the principal-agent problem and focus more on the true needs of the poor beneficiaries rather than the public preferences in affluent countries.

Aid for Trade must better connect to private-sector organizations, using web-based applications to assist local entrepreneurs. In this context, e-mentoring has become a promising tool to bring tacit knowledge and investment to growth-oriented entrepreneurs, facilitating more private-sector involvement. E-mentors from all over the world could assist a growing, young and educated generation of entrepreneurs in the developing world by providing expertise and supportive e-infrastructure.7

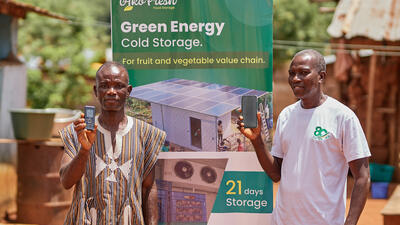

One innovative programme originates from the African Technology Development Forum (ATDF). The ATDF has designed a Matchmaking Platform (http://match.atdforum.org) to match local entrepreneurs with mentors who can represent potential problem-solvers, investors and business partners, or act in this capacity themselves, or both. E-expertise and support make up for lack of experience (tacit knowledge), create a supportive business network and enhance access to funding. Mentors are supported by mediating institutions on the ground.8

Mentoring organizations have expressed great interest in ATDF’s e-mentoring initiative. The Matchmaking Platform allows properly registered mentors to contact promising entrepreneurs directly and vice versa. Once there is a mutual interest to collaborate, entrepreneurship coaching institutions in developing countries and mentoring institutions in developed countries become active meditators on the ground and thus help ensure the quality and success of such joint projects initiated with private actors via an e-platform.

Even though many

entrepreneurs and mentors have already registered, operations are expected to

start in May 2011 when the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development,

the World Trade Institute and ITC meet with the Swiss Secretariat of Economic

Affairs to discuss funding over the next three years.

1Juma, C. (2011). The New Harvest: Agricultural

Innovation

in Africa. New York: Oxford University Press.

2Aerni, P. (2009). ‘What is Sustainable Agriculture? Empirical Evidence of Diverging Views in Switzerland and New Zealand’. Ecological Economics 68(6): 1872-1882.

3Aerni, P. & T. Bernauer, (2006). ‘Stakeholder attitudes towards GMOs in the Philippines, Mexico and South Africa: The issue of public trust’. World Development 34(3): 557-575.

4OECD/WTO (2009). Aid for Trade at a Glance 2009: Maintaining Momentum. Paris/Geneva.

5Aerni, P. (2006). ‘The Principal-Agent Problem in International Development Assistance and its Impact on Local Entrepreneurship in Africa: Time for New Approaches’. ATDF Journal 3(2): 27-33.

6Ibid.

7Hamilton, B.A. and T.A. Scandura (2003). ‘E-Mentoring: implications for organizational learning and development in a wired world’. Organizational Dynamics 31: 388-402.

8 Aerni, P. and D. Rüegger (forthcoming). ‘Making Use of E-mentoring to support Innovative Entrepreneurs in Africa’. In Thomas Cottier and Mira Burri: Trade in the Digital Age. New York: Cambridge University.