Turning challenges into opportunities

More importantly, for developing and least developed countries, they also have a major bearing on how governments design and implement development and poverty reduction strategies, and pursue sustainable, inclusive economic growth, both at home and in surrounding regions.

Fundamentally, global growth is increasingly dependent on the growth markets of the South. The Conference Board, a global analyst, reports that from 2006 to 2011, emerging market and developing economies accounted for 83% of growth in world GDP. Although this contribution is forecast to drop a little in 2012, growing markets in developing countries will remain critical to the world economy and will gain significance over the medium to long term. For example, The Conference Board also forecasts that by 2025, just five emerging markets – Brazil, China, India, Indonesia and the Russian Federation – will collectively account for more than half of all global growth.

The rise of the growth markets of the South has been complemented by increased interconnectedness among developing and least developed countries, as manifested through significantly higher trade, investment, capital, technology and labour flows, and by the emergence of new global value chains. Historically, developing countries have been located at the periphery of international trade in goods and services, but since the early 1990s, the South has moved closer to the centre of international trade and has emerged as a renewed and buoyant region. This is likely to be a permanent development rather than a transitional one, and it will create a new geography for international trade.

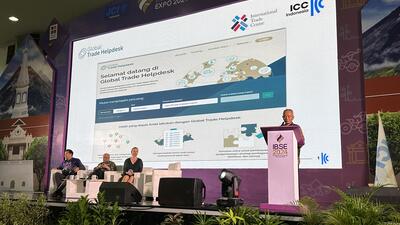

Indonesia is looking keenly at this opportunity. The country has the world’s 15th largest economy with a GDP (in purchasing power parity) of US$ 1.1 trillion. Global analysts, such as those from the McKinsey Global Institute, believe that Indonesia will be one of the world’s top 10 economies by 2030. In a September 2012 report, The Archipelago Economy: Unleashing Indonesia’s Potential, the McKinsey Global Institute estimates that Indonesia’s consuming class will grow from 50 million people today to 135 million by 2030, with 71% of the population in cities producing 86% of GDP. Indonesia’s economy will also provide a US$ 1.8 trillion market opportunity for consumer services, agriculture and fisheries, resources and education. Amid global economic challenges, Indonesia’s economy had already grown 6.3% by the middle of this year, compared to 6.4% in all of 2011.

With 240 million people, 50% of them younger than 29, Indonesia’s recent economic growth has been driven by a healthy combination of domestic consumption, investment and strategic government spending. Its export performance, currently contributing 26% to GDP according to Statistics Indonesia, is an important activity underpinning its economic development. The country has been focusing on exports of value-added products to further drive economic expansion and create a knowledge-based economy.

The Masterplan for Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesia’s Economic Development (MP3EI), which sets out six main economic corridors, provides all the necessary guidelines to expand the economy, such as increasing domestic market competitiveness. Anticipated internal growth has led to efforts to better connect Indonesia to other emerging economies. Through international trade Indonesia will be better prepared to cater to a growing population.

The country’s effort to move into non-traditional markets is accelerating with some success, and efforts are being made to develop South-South trade and diversify export markets. For example, in 2011, Statistics Indonesia reported that Indonesian exports to five major non-traditional export destinations – Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, South Africa and Peru – increased by 43%. This diversification recognizes that trade among developing countries represents promising economic opportunity and is a tool for strengthening world trade. The South must harvest opportunities at a time when the world economy faces greater uncertainties and emerging challenges that adversely affect their economies.

Transforming challenges into opportunities

Despite these advances, there are a number of challenges that developing and least developed countries must overcome in order to translate the new dynamics in global trade into inclusive and sustainable development. First, while there has undoubtedly been a shift in the world economic order, in recent decades output growth in the South has been uneven; where high growth has been seen, this has not necessarily reflected increases in productive capacity. As Supachai Panitchpakdi, Secretary-General of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, noted in this year's first issue of International Trade Forum, for many countries of the South the economic growth in the first decade of the new millennium was primarily driven by rising commodity prices and is not likely to be sustained over the long term. This is why Indonesia has embarked on an ambitious programme to move exports up the value chain and has introduced a number of initiatives to promote downstreaming. The aim is to make future generations of Indonesians less dependent on exports of physical resources, of which Indonesia has an abundance, and more reliant on high value-added exports of goods and services that draw on innovation and human capital as their source of competitiveness.

Second, looking at international trade, there is an exceptionally high level of import intensity in export production. In other words, strategic imports are essential inputs to the export process. This critical insight provides an understanding of the process necessary to climb up the value chain and how developing countries can stimulate growth in South-South trade with careful consideration in managing perceived and real barriers to trade.

No less important is the need to recognize inherent limitations in the nature and scope of South-South trade. Global value chains are still, for the most part, configured around meeting final demand in developed, industrial countries. Redirecting North-South supply chains’ trade away from North America and Europe to emerging growth markets is easier said than done, because despite the remarkable growth story, there is still an emerging consumer class with substantially less purchasing power than that in the industrial markets of the North. To meet the emerging demands of growth markets, the private sector will need to build global value chains centred on dynamic new products and services. This will require creativity, innovation, a greater emphasis on integrating small- and medium-sized enterprises in value chains, and the addition of local value as supply chains are reconfigured.

The way forward

At the heart of the discussion is the need to recalibrate global trade, find new ways to integrate growth markets more tightly in regional and global trade, drive improvements in competitiveness and connectivity, and distribute the benefits of closer economic integration fairly. In the past five years, the South has shown that it is the key driver in global economic growth. Governments, working together and with the private sector, need to build on this emerging dynamic and ensure the benefits of increased South-South trade are widely shared and support the broader development agenda of developing and least developed countries. The new geography of international trade is a necessary driver of global growth and a new economic architecture will define our collective resilience and the sustainability of our future.